Do we really understand what it is about university that benefits our students? Are our curricula designed to maximise student aspirational futures, or do we assume that will happen as a result of engaging with tried and tested models of traditional curricula?

In our last blog we introduced the term ‘constructive disalignment’ – where there is a disconnect between what a programme is designed to do and what stakeholders need it to do. A prominent example of disalignment is where educator and student perspectives on the purpose of the programme are ‘out of sync’; i.e. the programme outcomes chosen by the curriculum team are not built on a deep understanding of what will help graduates flourish personally and professionally. In this blog we explain the first stage of the framework – which is focused on the key question “What is the purpose of the programme?”. To help reflect on this question and identify key programme goals we have developed the MARVal framework.

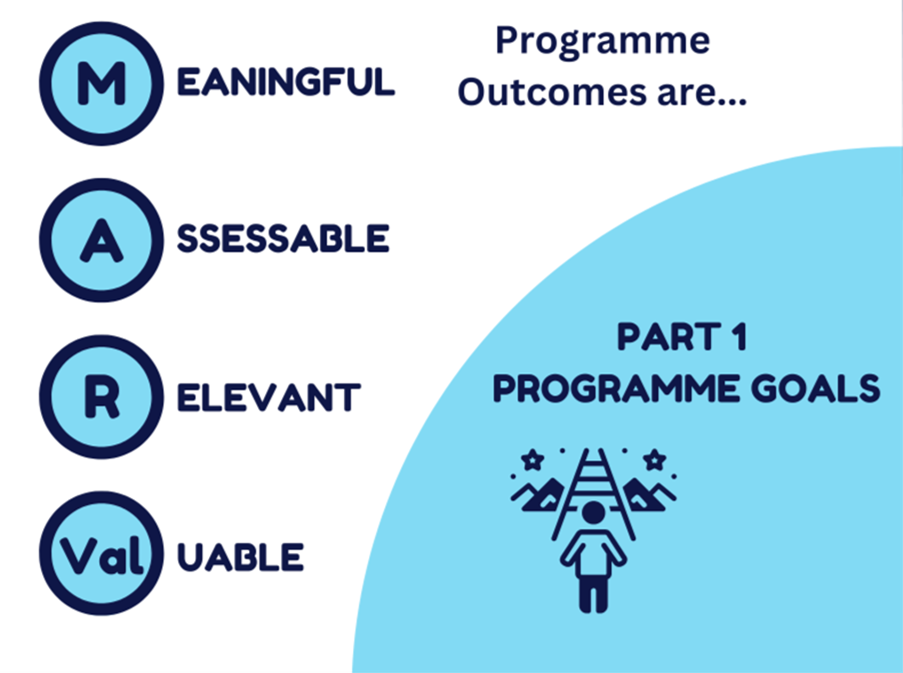

The MARVal Framework of Programme Competencies explained.

Identifying the core purpose(s) of the programme is essential. It’s more than the traditional disciplinary-focused statements such as “We teach students about Zeepium or “We teach students how to be Zeepiumists”. Students take on significant personal and financial costs as a way of investing in their future. Therefore, it’s vital to ensure that the purpose of a programme is directly aligned to what the students want/need the purpose to be (their aspirational future). A programme can be extremely well taught by the best educators yet still be constructively disaligned. As we mentioned in our second blog, a root cause of constructive disalignment is the large number of degrees that are not built from an assumption they are supposed to enhance each student’s personal and professional futures. You may be providing a fantastically taught programme incorporating cutting edge research for your students to become future Zeepiumists but if it results in any of the following, it is not aligned with its purpose:

- Underemployment because there are very few jobs as Zeepiumists, or graduate competencies have limited overlap with those required for their aspirational futures.

- Problems and delays creating a professional identity because students are unaware of their options and how to successfully achieve them; or how to navigate an increasingly unforgiving job seeker environment that relies on greater social capital or individual brand approaches to work.

- Graduates that struggle to flourish within their personal or professional lives, because the programme has been too focused on what students know (and a lesser extent what they can do), instead of helping them become who/what they want to be.

- Disatisfaction because students thought the degree would lead to something that it doesn’t or only leads to something that they don’t want to do (e.g. being a full-time Zeepiumist).

- Students that do not have the self-efficacy and adaptability to flourish in the environments they graduate into.

So how can we achieve what we identify as being ‘authentic’ constructive alignment?

To be effective, the whole curriculum (including assessment and marking criteria) should aim to be constructively aligned to programme outcomes that are MARVal-ous (Meaningful, Assessable, Relevant and Valuable). We are going to present them in a slightly different order here for you.

Relevant – Built on a detailed understanding of student aspirations, motivations and prior experiences. We recognise that university education is about much more than facilitating career development, so programme outcomes should be relevant to holistic student futures. However, the only way to find out what outcomes are relevant for your students is to understand their motivations, aspirations and past experiences.

Valuable – Built on a detailed understanding of the environment that student will have to achieve their aspirational futures in. In the previous blog, we highlighted multiple reports evidencing skills gaps across multiple sectors. A common thread across these reports is that graduates would benefit from more transferable skills, interdisciplinary ways of working and a positive ‘growth mindset’. We suggest that this is, at least partially, because curriculum design teams would benefit from more engagement with stakeholders that have lived experience of student’s aspirational futures (and not just academic experience).

To clarify the difference between Relevant and Valuable. The student decides the Relevance because they own their future. The world outside of the university decides the Value, because they are usually best placed to define what is necessary for success in the student’s future.

Meaningful – Everyone (different educators, students, society and potential employers) understand how each outcome has been evidenced within the curriculum and how it can be applied in relevant and valuable contexts after graduation. What graduates will develop should be conceptualised in a way that considers how they will be used in the future.

Assessable – There must be some form of activity or output that allows students to evidence that they have achieved the programme outcomes and a way of grading the level of achievement. We recognise that some outcomes are immensely invaluable but difficult to evidence. For example, developing a ‘growth mindset’ and professional autonomy are key components of employability and general wellbeing, but are very difficult to teach or assess in a traditional context. So, when considering outcomes, we need to think about how we are going to grade student attainment of them. For example, how do we articulate levels of achievement of an attribute such as ‘autonomy’?

The implications of MARVal

Universities owe students more than a ‘piece of paper’. We believe the future of the sector lies in curricula that are co-created with students and stakeholders, grounded in real-world relevance, and designed to empower graduates to thrive in complex, evolving environments. To get there, we need to move beyond traditional models—towards programmes that are responsive to student aspirations, informed by lived experience, and transparent in their purpose and impact.

Questions for you to consider.

- How well do your current programme outcomes reflect what your students truly aspire to—and how do you know?

- Whose voices are shaping your understanding of what’s valuable for your graduates’ futures—and who might be missing?

- Can every outcome in your curriculum be clearly explained, applied, and assessed in ways that matter beyond graduation?

Explore more practical tools and insights on our website to help you design outcomes that are Relevant, Valuable, Meaningful, and Assessable.